There ain’t nothin sweeter than ridin the rails. — Tom Waits

Several years ago while on vacation, back before we moved to Colorado, back before this blog was nary a glimmer in my eye, I did a mountain bike ride near Salida called the Alpine Tunnel loop. I remember it being an enjoyable high-altitude outing that takes in historical sites, old railroad grades, and a spectacular, seldom-travelled section of the Continental Divide Trail. Since then, I’ve occasionally thought of doing it again, then would promptly forget about it while occupying myself with the multitude of other outdoor activities in the area.

This past week, the memory of that ride found its way into my brain again. With the unusually dry, mild fall making access to the high country still possible in mid-October, I decided it was time to give it another go.

I first checked a map to re-acquaint myself with the route. Most people do this ride starting in the ghost town of St. Elmo. When I last did it, I moved the start down the hill to just above Mt. Princeton Hot Springs. This allows you to take in a second segment of railroad grade and to enjoy the long gravel spin up to St. Elmo as a warm up. At 35 miles and over 4,000 feet of climbing, it’s a longish ride but because the majority of the climbing is on an old train route — steel wheels on steel rails don’t do steep hills — it’s gradual and quite pleasant. The sort of long, mixed-terrain outing I really enjoy.

What makes the ride unique are those two old mining-era railroad grades, open only to non-motorized traffic, including its namesake, the Alpine Tunnel Trail.

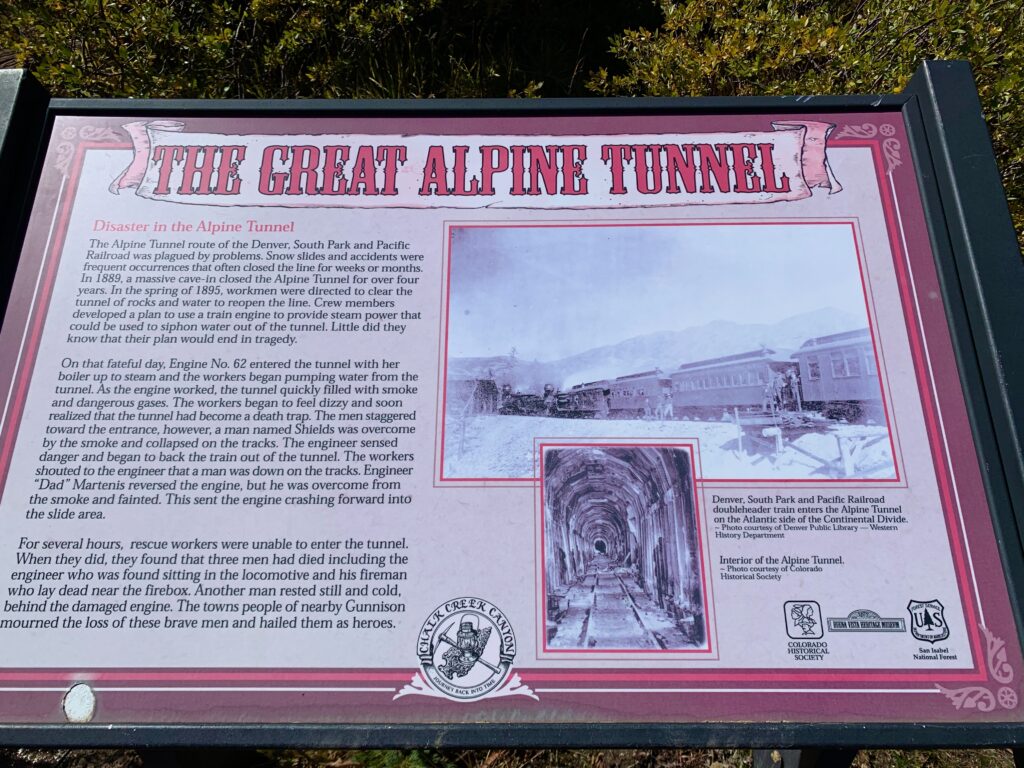

The Alpine Tunnel Trail is a 2.5-mile segment of the old Denver, South Park and Pacific railroad grade running from the historic townsite of Hancock up to the east portal of the Alpine Tunnel. The Alpine Tunnel is a 1,772 ft. long narrow-gauge railroad tunnel built through the Continental Divide at an elevation of 11,523 feet. It was originally built to carry gold ore from the mines near St. Elmo and Hancock to processing plants on the western slope. Construction of the tunnel began in 1880. When it was completed in 1882, it was the highest railroad tunnel in North America.

The tunnel remained in operation from 1882 until 1910 when, due to diminishing ore production from the local mines and the high cost of maintaining the tunnel, it was abandoned. It is believed the tunnel caved in sometime in the 1930s but it wasn’t until the 1990s when it was officially sealed off for safety reasons.

The other railroad grade is at the start of the ride. On the mountainside overlooking Chalk Creek, across from the Chalk Cliffs, is a two-mile segment of the same narrow-gauge railroad grade that used to go up to the Alpine Tunnel. Near to both Salida and Buena Vista, it’s a popular trail for day hikers.

Nice view of the Chalk Cliffs from the parking lot.

For the most part, the trail is smooth and wide. Even though it’s uphill, the grade is so gradual, it’s barely perceptible to the legs.

It’s mid-October and most of the aspens have lost their leaves but at lower elevations there are still splashes of gold from cottonwoods and other trees.

The mighty Mt. Princeton keeps watch from the north.

Chalk Lake

Chalk Creek Cascade

Just above the cascade, the railroad grade connects with County Road 162, which was itself built on the original railroad route. Now a road, it’s a smooth, gentle gravel spin all the way up to St. Elmo.

Alpine Lake

Shortly before St. Elmo the road to Hancock forks off to the left. The Hancock Road is two-wheel drive but it’s noticeably narrower and rougher than the St. Elmo Road. I know for a fact it’s two-wheel drive because one summer before we moved to Colorado the wife and I drove a standard rental sedan up to Hancock as part of a sight seeing trip. Don’t tell the folks at the Denver Airport Avis.

Abandoned railroad trestle over Pomeroy Creek

Old ore house for the Allie-Belle mine. This thing has been gradually falling down for something like 150 years.

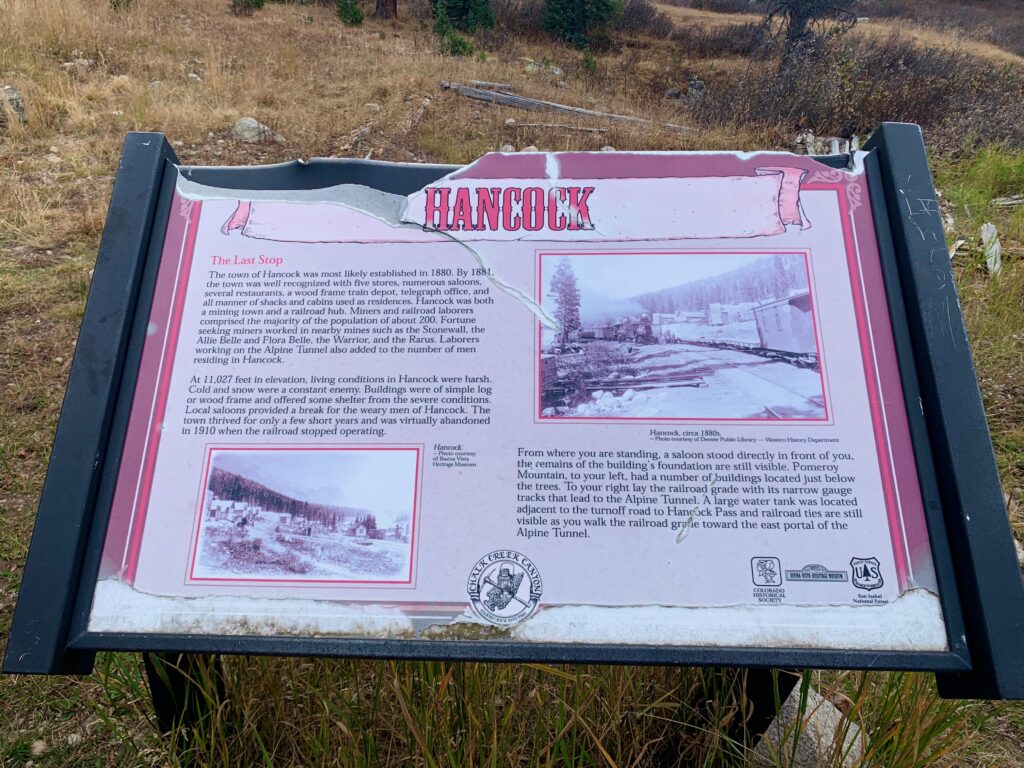

The Hancock town sight. Back in the 1880s this place was a town of 200 people, mostly miners and railroad workers. Now the only thing left are pieces of the foundation of the old saloon. Which somehow seems fitting. There probably wasn’t a lot to do at 11,000 feet in the winter except drink at the saloon.

Starting up the Alpine Tunnel Trail. On some of the lower sections you can still see the old railroad ties that used to hold the tracks.

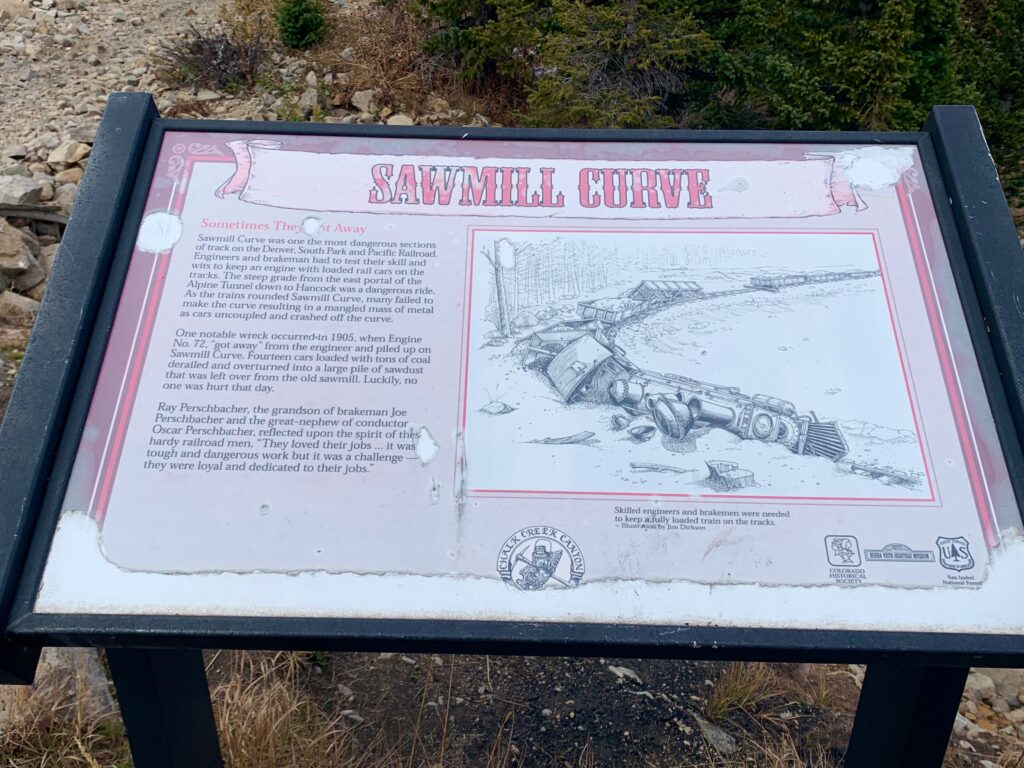

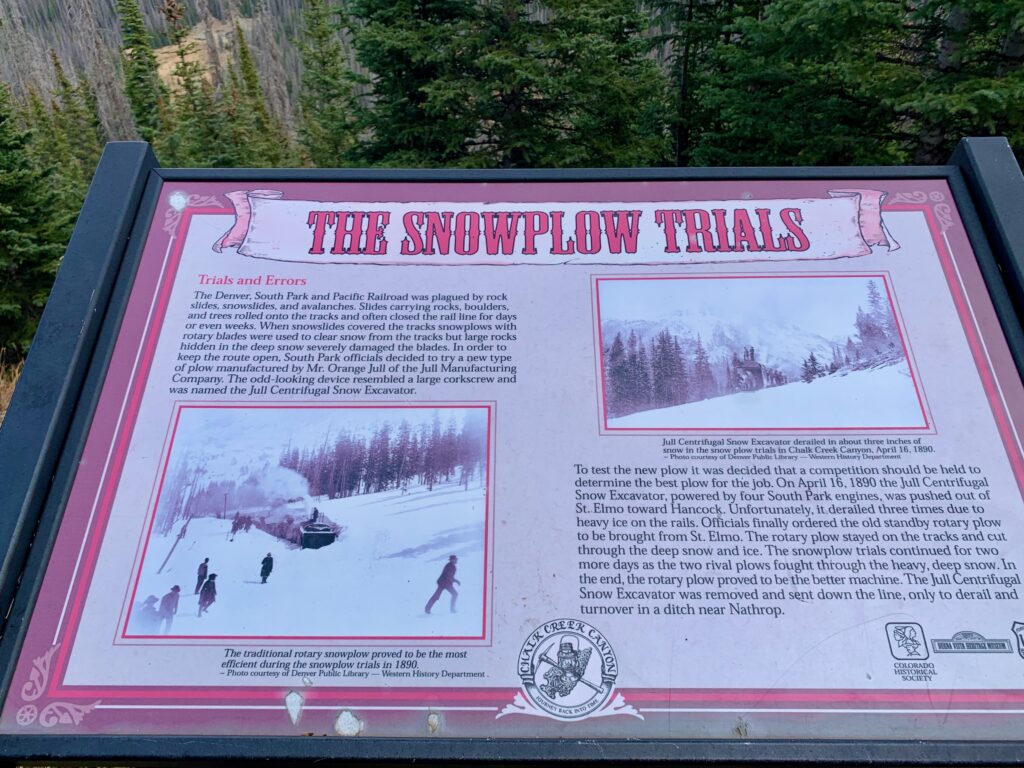

Some history lessons along the way.

My destination, the Continental Divide, straight ahead.

Maybe a hundred yards before the east portal of the Alpine Tunnel, the Continental Divide Trail splits off to the left and starts a steep climb up the ridge. Because there’s nothing to see at the east portal but a pile of rocks, I didn’t feel like making the side trip through the willows up to it. But here are a couple of photos from a summer hike when I did.

The climb up the ridge from the tunnel is short but steep, mostly hike-a-bike. Because no bike adventure is complete without some hike-a-bike.

Top of the Continental Divide. The highpoint of the ride, from both an enjoyment and a topographic standpoint. You follow the CDT north for five miles through three high alpine basins, all above 12,000 feet. The trail is up and down, although I must say, it seemed a lot climbier than I remembered. Beautiful, high alpine riding.

There are several creek crossings, all flowing even in late fall. Kind of remarkable considering there’s no snow to melt and with the Continental Divide immediately on your left, the water isn’t coming from somewhere else. It starts right here, in these basins. Clearly from natural springs.

The picturesque Tunnel Lake.

Climbing out of the first basin.

And descending into the second.

Dropping into the third basin, Tin Cup Pass. Tin Cup Peak is left of center. You can just see the four-wheel-drive road switchbacking over Tin Cup Pass on its left shoulder.

Descending back into the trees and some of the smoothest, sweetest single track I’ve ridden in a long time.

Creek crossing just before joining Tin Cup Pass road.

Tin Cup Pass Road is a rugged four-wheel drive road that takes you back down to St. Elmo. No pictures, because I was having way too much fun flying over rocks and launching off water bars. The best part, I passed two vehicles — an ATV and a lifted Ford F-150 — slowly picking their way through the rocks on the way down. On your left!

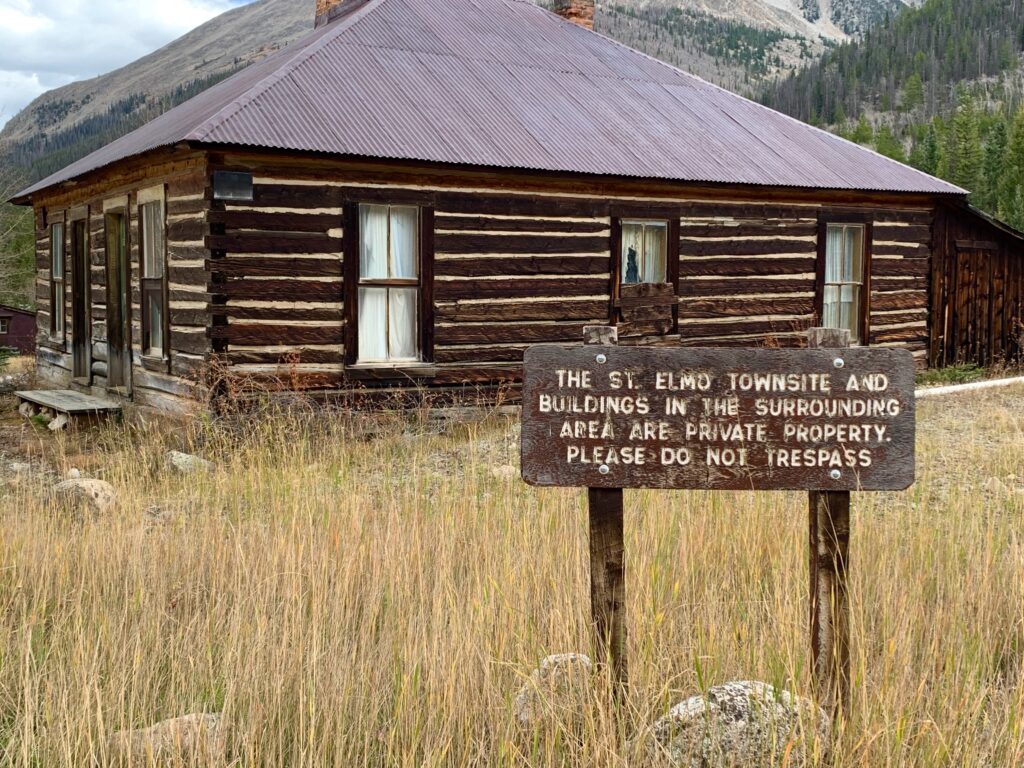

Back down at St. Elmo. I took a break to rest my arms and legs and to watch the tourists feeding the chipmunks on main street.

From St. Elmo it’s a smooth, high-speed descent on gravel back down CR 162 to the railroad grade where I started.

After I got home, I looked through my photo files to see exactly when I first did this ride. To my astonishment it was 2009, fifteen years ago! No wonder the CDT seemed more climby this time around. I know I’m better acclimated to altitude than I was back then but I’m also sure my fifteen-year younger legs could put out a few more watts than I’m capable of now.

Regardless, it’s still a great ride. Glad I finally got back up there to do it. The crisp fall air, the natural beauty and the satisfaction of physical effort are stuff that sustains the soul.

I’m sure that riding a bike on the rails isn’t what Mr. Waits had in mind, but I have to say, it’s still pretty dang sweet.